Category: Aviation

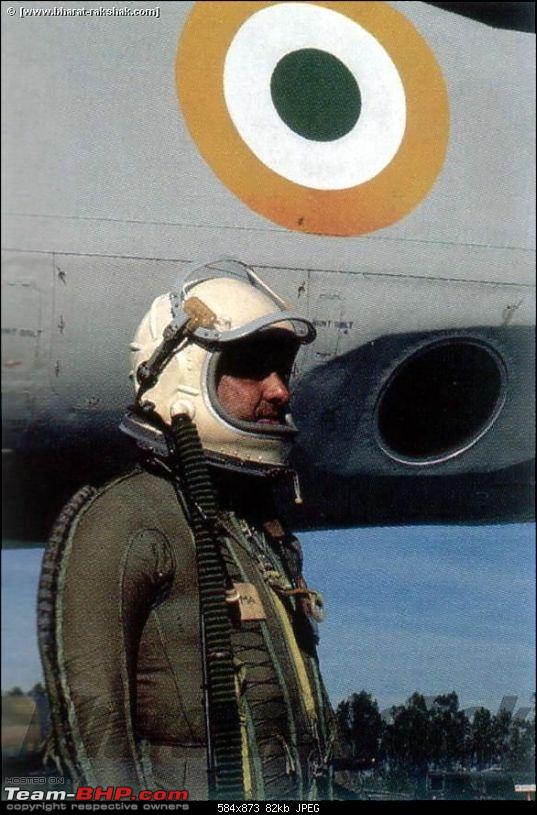

Loneliness at Mach 3: Interview with a MiG-25 Foxbat pilot

High-flying, insanely fast and untouchable, the MiG-25R Foxbat served the Indian Air Force with aplomb. We spoke to Air Marshal Sumit Mukerji about flying the world’s fastest operational aircraft.

What aircraft did you fly and how many hours do you have on type ?

“I retired 7 years ago at the age of 60, with over 3,400 hrs on jets. I had the distinction of Commanding three units. First, a MiG-29 Squadron, second a MiG-25R Squadron and lastly the Tactics and Combat Development Establishment (TACDE) – the ‘Top Gun’ school of the IAF – which had the MiG-21, MiG-23U and the MiG-27. So, as a historical landmark, I am the only pilot in the Indian Air Force (and probably the Russian Air Force ?) to have ‘Commanded’ units with the MiG-21, MiG-23U, MiG-25R, MiG-27, MiG-29.”

What were your first impressions of flying the MiG-25R ?

“A 20-ton aircraft that carries 20 tons of fuel, flies in the stratosphere, cruises at Mach 2.5 in minimum afterburner and exceeds Mach 3.0 with ease when required, what can one say ? It was an awesome aeroplane. The fact that the ventral fuel tank was one MiG-23 (equivalent in fuel) under the belly, speaks for itself.”

Which words best describe the MiG-25 ?

“Catch me if you can”

What is the cockpit like and how pilot-friendly is it ?

“Most Russian aircraft cockpits evoke a feeling of comfort and familiarity to a pilot who has flown Russian aircraft before. Coming from the MiG-21 to the MiG-25R was an easy transition. As one of our Air Chief’s remarked when the aircraft was demonstrated to him and he was stepping into the cockpit, “This is rather familiar. And dammit, it even smells the same!” The cockpit was a little more spacious than the MiG-21, thankfully so, because we operated wearing the pressure suit (which, incidentally, was the same as that worn by Yuri Gagarin – so much for Russian sustainability and dependability).

The two-seater (or Trainer version) was unique. It is the only aircraft I know (other than the Tiger Moth, I guess) where the trainee sits in the rear seat. The design, to my mind, was an aeronautical engineering masterpiece. To put it rather simplistically, the camera block was removed from a single-seater and a cockpit created in that space. The canopy, although the same as the other cockpit, appeared ‘flushed’ with the nose of the fuselage, as viewed from the rear cockpit. Thus the trainee felt he was sitting in a single-seater when in the trainer. The transition to going ‘solo’ was a piece of cake. With the nose-wheel located behind the rear cockpit, a 90 deg turn onto a taxi track entailed the front cockpit extending over onto the grass beyond the taxi track (at the ‘T’) before the turn was executed. A little unnerving initially for anyone (though airline pilots may not have felt uncomfortable).”

Read about flying and fighting in the MiG-27 here.

What can you say about the performance of the MiG-25 ?

“It was a beast with immense power. It has been described by some as ‘an engine with place for a pilot and some avionics’. The Tumansky R-15B engines each provided more than 10 tons of thrust to produce the desired performance. In almost all the other aircraft I have flown, a regular climb was executed at constant TAS (True Air Speed, the speed of the aircraft relative to the airmass in which it is flying) with a progressive reduction of IAS as the altitude increased. The Foxbat climbs at constant IAS with an increasing TAS, crossing abeam the take-off dumbbell (if a reciprocal turn were to be executed after take-off), at 30,000 ft and increasing! She would be crossing 20km (65,000 ft) in 6.5 minutes from wheels-roll, at a rate of climb (ROC) of 100 m/sec (almost 20,000 ft/min) ‘like a bat out of hell’, if you did not come back from the Max afterburner regime – In comparison, the ROC of a MiG-21 was 110 m/sec at sea-level. Now, that is sheer performance. Cruising at 20+ kms with minimum afterburner (which, incidentally, provided best specific fuel consumption) she could execute a 45-50 deg bank turn with just a wee bit of additional power. There was no loss of height. Her systems and auto-pilot were coupled to provide an optimised “Little m=1” (remember the formula for maximum range ?). So, as the fuel depleted she would keep climbing (cruise climb) and a mission commenced at (say) 19.5 kms altitude would terminate around 22 kms with no change of throttle position. The climb was so gradual over the period of time and distance that it did not affect the photography.”

What was the pilot workload ?

“With virtually a first generation inertial navigation system (coupled with the ground beacon RSBN), one could engage the auto-pilot at 50m (165 ft) after take-off and take your hands off the control column. The Foxbat would execute the complete mission, photography included, and return to base (or programmed airfield) descending to a height of 50m when the pilot needed to take control and flare out for a landing. All that the pilot was required to do through the entire mission was manipulate the throttle – From max afterburner at take-off, to min afterburner at about 60,000 ft, to idle throttle setting approximately 350 Kms from landing base (the MiG-25 would glide the distance), to 75% RPM on top of approach to landing. That’s it !”

Were you detectable by radar ? Were you susceptible to interception ?

“Certainly we were detectable by radar, provided you were expecting us. The Foxbat operated covertly, seen just as a blip on the radar amongst other flying aircraft, but one blip would suddenly disappear. In normal ground radar settings the Foxbat generally operates at the highest fringes of the radar lobe, with the ingress and egress (through the radar lobe) often allowing one or two blips for the radar controller to perceive. Low transition times (because of the high speed) did not provide adequate reaction time to scramble fighters; and other than a pure head-on interception with look-up / shoot-up capability (from, say, 40,000 ft), the Foxbat could survive any fighter interception.”

Read about flying and fighting in the MiG-21 here

What were the limitations of the aircraft ?

“The fuel quantity, I guess. The engines were gas guzzlers and 20 tons of fuel (including the ventral tank and fuel in the vertical fins) was just adequate. In the regional perspective of India and its neighbours it would suffice but we always returned for landing with 200-400 kg of fuel remainder (200-250 kgs was the fuel required to execute one circuit and landing). We operated on the fringe. The runway had to be kept clear at landing base (no other flying permitted for fear of runway blockage) once the MiG-25 commenced his descent. We needed to give only three R/T calls – one for take-off, one for commencing descent and one for landing (in operational missions just two). There was no need to give any other R/T calls because you operated unhindered in the stratosphere.”

What does operating in the stratosphere feel like?

“The subtle change in the colour of the sky starts around 16 kms (50,000 ft), I guess, as the suspended particles which reflect / refract the sunlight start getting dissipated. The sky turns a distinct grey as you cross 20 Kms (65,000 ft) and continues getting darker as you transcend into those dizzying altitudes of 90,000 ft and 100,000 ft. You fly with cockpit lighting ‘ON’ (as for night flying). It is a little eerie, one must admit. Not natural. The earth is round, a fact we could confirm (!) because you can see the curvature of the earth very clearly from those altitudes. The sun, moon, stars and the illuminated ground below, are all visible at the same time. A glorious feeling.”

What special clothing did you need and how effective was it ?

“As mentioned earlier, the pilots used the same pressure suit that Yuri Gagarin wore as the first man in space. The suit was the same that was supplied to MiG-21 and MiG-23MF pilots for their high altitude interception roles. It was not the most comfortable of suits but then pressure suits had a purpose. One needed to wear silk ‘inners’ (full sleeve top and ‘long-john’ lower pants) to allow the skin-tight suit to be put on. Needless to say, it required the help of another person (trained airman) to assist the pilot. Once zipped up (suggest one uses the washroom before donning the suit), there was further tightening of the suit by means of laces (on the chest, belly, back, legs, arms) to ensure the tightest fit without causing breathing discomfort. It was difficult to tie your own shoe laces. The neck-ring (on which the helmet would be put and locked – it weighed 2.5 Kgs) had this latex bladder which came over the head and distributed around the neck, not unlike a condom. Over the pressure suit the pilot would wear a loose flight suit to obviate the snagging of the pressure suit laces with switches / levers in the cockpit.”

“All this was fine in winters, but in summer, with the ambient temperature close to 40 deg C (104 deg F), the cockpit conditions with the canopy closed was a killer (start up time to take off approx 20 mts). Like other MiG aircraft, the heating system was brilliant, but the cooling system was designed to cut in only at 1 Km above ground level (and cut out at the same height during the return). Four layers of clothing – underwear, silk inners, pressure suit, flight suit – in those temperatures, meant you were soaked to the skin by the time you returned to the aircrew room. It needed an extra effort by the trained assistant to peel the wet pressure suit and wet inners off your body. Guess we got our share of sauna baths!”

What were your biggest fears in flying the MiG-25 or were there none?

“When you are flying a virtual fuel tank, the biggest fear is the illumination of the “Fire” warning lamp. This was more so at operating altitudes in the stratosphere. The ejection seat in the MiG-25 was the same as that in the later models of the MiG-21 and MiG-23. The ejection seat had two settings (3 Kms / 10,000 ft and 6 Kms / 20,000 ft), to be set depending upon the terrain one was operating over. We set ours to 6 Kms. But operating at (say) 20-22 Kms altitude, where the ambient temperatures are around minus 85 deg C, an ejection meant a free-fall of 15 Kms (50,000 ft) before the seat separated and activated the parachute. Would you hit terminal velocity ? I guess you would. It was not a happy thought.

The other fear was that, God forbid, one had to eject over enemy territory. On landing, how fast could one get out of the pressure suit (without external help) and be unbridled and unhampered to scramble for an escape ? We practiced and mastered the art in the squadron.”

What improvements would you have liked incorporated in the aircraft?

“An in-flight refuelling system (but in those days the IAF never had an AAR /FRA) to increase its potential. Digitisation of its photo and ELINT systems could have upgraded the aircraft and extended its life for another decade at least.”

Can you tell us of any specific reconnaissance mission which produced exceptional results ?

“Well, the photographs of the mountains and the terrain in the Kargil sector (15-18,000 ft) during the Indo-Pak Kargil conflict of 1999 are testimony to the photographic quality obtained from the MiG-25R. Every ridge, every crevasse, every approach and defile was clearly defined, all enemy positions and bunkers in the craggy and inhospitable mountain ranges lay exposed, providing immense information to the Indian Army and the IAF to conduct successful operations.”

Flying and fighting the MiG-19 here.

Can you describe any notable mission you have flown ?

“On 24 October 1995 the world witnessed a total solar eclipse and the path of the shadow traversed through North India. The Udaipur Solar Observatory requested the IAF to photograph the eclipse from the stratosphere, an exercise (to our knowledge) never done before. The purpose was twofold – to photograph the eclipse as it progressed, with a front looking camera in the cockpit and secondly, to photograph the traverse of the shadow over the surface of the earth, with the belly cameras. The high resolution, single-shot Hasselblad camera (20-25 frames/sec) provided for the front photography was a monster. It had to be fitted on top of the instrument panel and it blocked the forward visibility of the pilot. It was decided to use the two-seater and fit the camera in the front cockpit. The fitment, as any aviator would know, was a major task. Alignment with respect to the flight axis of the aircraft (angle of attack in flight) and the position of the sun was a major exercise. Scientists of astronomy from the Solar Observatory

The ’starburst’ as captured by the MiG-25. The aircraft has been superimposed go give the effect to the article publicising the event. It was discussed by Bhatnagar, A & Livingston, William Charles, in Fundamentals of Solar Astronomy (2005). World Scientific. p. 157. ISBN 9812382445.)

obtained charts from NASA (also) to determine the ambient conditions likely to prevail in the stratosphere at the appointed time and altitude. It was decided (scientifically) that an altitude of 24.5 Kms (80,000 ft) and a speed of 2.5M flown towards the sun (in the path of the shadow), would provide the desired results. After fitment of the camera, the aircraft had to be raised on jacks, wheels retracted to simulate flight conditions and a framework fabricated with a simulated sun erected in front at a prescribed distance to get the correct alignments. For eye protection it was necessary to fly with the seat fully lowered which posed a problem of tracking the sun accurately with respect to the camera. So we fabricated a “gun sight” for the rear cockpit. A small aluminium frame with a 2cm x 2cm window over which a graph paper was pasted constituted the gun sight. The centre of this graph paper (the point of origin) was where the sun had to be maintained. This point had to be ‘harmonised’ with the camera, a procedure familiar for fighter pilots of that generation. Special filters to protect us from the damaging rays of the sun had been obtained from Argentina and Mexico. These were pasted over the visor of the pressure helmet.

As luck would have it, the scientists discovered that about 8-10 days before D-Day, the moon was going to be in exactly the same position as the predicted sun position on the day of the total solar eclipse. It was an opportunity of a lifetime to get a practice mission, albeit at night. The time worked out by the scientists was 2335 hrs or so (if I remember right). The mission was flown and while the daylight camera could not provide the clarity, the alignments and the ‘gun sight’ were verified and fine tuned.

On the day of the eclipse, at the pre-determined time, two MiG-25s, the MiG-25UB (two-seater) and a MiG-25R (to photograph the shadow) took off with the MiG-25R trailing 2 minutes behind. Timings were critical and they were met. We fed into the predicted path of the eclipse and started our photography about two minutes before the total eclipse took place. While it was getting darker by the moment, when the total eclipse took place we were enveloped in absolute pitch black conditions and the stars had a clarity and luminosity not seen otherwise. Everything was as per plan. The “gun sight” worked ! While the total eclipse was viewed from the ground for 42 secs, flying at 2.5M towards the sun allowed us to view the total eclipse for 2 minutes and 25 seconds. The changes in the corona surrounding the sun in this period of the total eclipse were of immense value to the scientists, because with no suspended particles the clarity of the photographs was beyond their expectations. The “Diamond Ring” (the most popular photograph during an eclipse) was indeed delightful to see, but the ‘Piece de Resistance’ followed immediately afterwards – the “Starburst”, as the sun peeped through the ridges on the surface of the moon (the photograph is attached). An unusual mission but an experience of a lifetime.

Was the MiG-25 comfortable to fly after the MiG-21 ?

“A bullock cart, we would joke. She was heavy but responsive. Because of the weight there was a lot of inertia, requiring anticipation. To the ab-initio the aircraft would wallow on approach, if pilot anticipation and control input were not timely. She was steady as a rock during the climb and its stated mission profile. The two-seater was aerobatic and we did rolls, barrel rolls and rolls-off-the-top. The loop was prohibited because there was apparently inadequate elevator available to pull her through the manoeuvre. Ground handling was outstanding.”

Did you ever practice combat training – Practice Interceptions, etc ?

“The IAF MiG-25R was a purely reconnaissance version. PIs were conducted on us during various exercises. There were no successful interceptions to my knowledge.”

How difficult were the maintenance practices on the MiG-25R ?

“It was my first experience with (virtually) a modular concept of maintenance. Coming from the MiG-21 it was a pleasure to see the ease with which those massive engines of the Foxbat could be changed. The camera block lowered with winches and pulleys easily. The ELINT system was easily accessible. Because of its size, technicians could crawl in and out from access points for ease of maintenance.

Read about flying the B-52 here.

Sure, you can call it an ‘archaic, unsophisticated machine’. But then there was no other ‘sophisticated’ aircraft to either match its performance or shoot it down ! With a navigation accuracy of (max) 10 kms off track over 1000 kms (with a lateral photo swath of 90 kms), strategic targets were never missed. It was amazing for its role.

We had problems with the tyres and the fuel in the initial years. The Russians did not clear the Dunlop manufactured tyres nor the Indian Oil manufactured aviation fuel for quite some time. We remained dependent on the USSR for the supply of these two major items. The on-going Iran-Iraq war curtailed supply through the Suez Canal. So our fuel and tyres would come by ship, around the Cape of Good Hope. This led to restrictions in our quantum of flying. The aviation fuel, as you would expect, had to be different from the regular aviation fuel. Regular aircraft were using fuel K-50 (Nomenclature for aviation fuel with SG 0.77) while we required fuel K-60 (Nomenclature for aviation fuel with SG 0.84). The higher specific gravity was essential to raise the flashpoint of the fuel because skin temperatures on the aircraft would exceed 300 deg C (ambient temp minus 85 deg C).

The high temperatures also necessitated good cooling systems for the avionics and cameras. This was achieved by alcohol (98 proof !). The MiG-25 consumes almost 200 litres of alcohol per mission. Alcohol bowsers (tankers) were provided for replenishment which had a ‘tap’ provided at the rear (Aah ! Don’t you just love the Russians ?) – for purposes best left to your imagination! (venting, perhaps!).”

Read about Flying and fighting in the English Electric Lightning here

For an operational mission what would be the approximate timeframes from receipt of task to the completion of photo processing ?

“Well, the MiG-25R was designed to carry out strategic reconnaissance. Targets for such missions are not generally time constrained as in tactical scenarios. However, if it came to a pinch, it would take about two hours of manual panning (with necessary intelligence inputs) on maps, feeding the way-points in binary onto the plates and running it through the ground testing system to check the veracity. Pilot briefing is concurrent because there are other pilots assisting with the map planning. ELINT programming would also be concurrent. Then the plates are slotted into the aircraft and the inertial platform erected (energised). This would typically take about 30 mins in winter and 45 mins in summer. During this time the pilot would be assisted into his pressure suit and he would proceed to the aircraft. From start to take off we may consider 15 mins and a one hour mission thereafter. Once on ground, the camera spools would be off-loaded (simple procedure) and their analog processing in the dark room commenced. The specialist photo-interpreter would view the semi-dry negatives, identify the frames with the required targets and these would go into print positives. Thus the post flight procedure would also take roughly two hours. It would be safe to assume a mission, from start to finish would take about six hours. Add two more for delivery to the user. ELINT decoding would be simultaneous and coincidental to the photo processing.”

Were any special qualifications required to become a MiG-25 pilot ?

“Not really. However, all pilots had extensive experience on MiG-21s.”

After the MiG-25 how did it feel to fly any other fighter ?

“They were all sports models! Perhaps the greatest joy was to be able to throw the fighter around in the sky with gay abandon (which you missed when you flew the Foxbat), do aerobatics, fire weapons and the adrenalin of doing air combat. We missed the ‘G’ ! Also the sheer thrill of seeing another aircraft in the same sky!”

Dear reader,

This site is in danger due to a lack of funding, if you enjoyed this article and wish to donate you may do it here. Even the price of a coffee a month could do wonders. Your donations keep this going. Thank you.

Were you ever concerned about enemy defences ? What actions would be initiated if you were painted on enemy radar?

“It would be naïve of any warrior not to be concerned about his enemy. As I have mentioned before, missions were covert and silent. Just two R/T calls – for take-off and landing. There were no warning systems in the aircraft. The only warning that could be given was by our own ground radar picking up a possible interception. Depending upon the threat, it would entail moving the throttle up the quadrant and initiating a gentle climb. Secrecy, speed and altitude were our only weapons.”

Read about flying the Mirage 2000 here

Were there any aero-medical aspects that affected pilots flying aircraft such as these ?

“We were subjected to aero-medical scrutiny for the first year of operation of the aircraft. There were two issues of concern to the doctors. Firstly, the extent of exposure to UV Rays because of the clarity of the troposphere. We were made to carry dosimeters on our person. The results indicated there was no cause for concern. The second was the phenomena of possible ‘Disassociation’ (In psychology, ‘disassociation’ entails experiences from mild ‘detachment’ from immediate surroundings to more severe detachment from physical and emotional experiences – phenomena involves a detachment from reality —– Wikipedia). This came into consideration because of the rather lonely and silent missions in the troposphere, detached and distant from regular flight profiles. The issue was discounted because of the relative short duration of the missions – one hour at best.”

Some parting words?

“The MiG-25R was a superb flying machine, eminently suited to its task. It provided a feeling of immense power, invincibility and supreme confidence to the pilot in the execution of his mission.”

You may enjoy these articles:Interview with USAF spy pilot here

Top Combat Aircraft of 2030, The Ultimate World War I Fighters, Saab Draken: Swedish Stealth fighter?, Flying and fighting in the MiG-27: Interview with a MiG pilot, Project Tempest: Musings on Britain’s new superfighter project, Top 10 carrier fighters 2018, Ten most important fighter aircraft guns

“If you have any interest in aviation, you’ll be surprised, entertained and fascinated by Hush-Kit – the world’s best aviation blog”. Rowland White, author of the best-selling ‘Vulcan 607’

I’ve selected the richest juiciest cuts of Hush-Kit, added a huge slab of new unpublished material, and with Unbound, I want to create a beautiful coffee-table book. Pre-order your copy now right here

“If you have any interest in aviation, you’ll be surprised, entertained and fascinated by Hush-Kit – the world’s best aviation blog”. Rowland White, author of the best-selling ‘Vulcan 607’

I’ve selected the richest juiciest cuts of Hush-Kit, added a huge slab of new unpublished material, and with Unbound, I want to create a beautiful coffee-table book. Pre-order your copy now right here

TO AVOID DISAPPOINTMENT PRE-ORDER YOUR COPY NOW

From the cocaine, blood and flying scarves of World War One dogfighting to the dark arts of modern air combat, here is an enthralling ode to these brutally exciting killing machines.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes is a beautifully designed, highly visual, collection of the best articles from the fascinating world of military aviation –hand-picked from the highly acclaimed Hush-kit online magazine (and mixed with a heavy punch of new exclusive material). It is packed with a feast of material, ranging from interviews with fighter pilots (including the English Electric Lightning, stealthy F-35B and Mach 3 MiG-25 ‘Foxbat’), to wicked satire, expert historical analysis, top 10s and all manner of things aeronautical, from the site described as:

“the thinking-man’s Top Gear… but for planes”.

The solid well-researched information about aeroplanes is brilliantly combined with an irreverent attitude and real insight into the dangerous romantic world of combat aircraft.

FEATURING

From the cocaine, blood and flying scarves of World War One dogfighting to the dark arts of modern air combat, here is an enthralling ode to these brutally exciting killing machines.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes is a beautifully designed, highly visual, collection of the best articles from the fascinating world of military aviation –hand-picked from the highly acclaimed Hush-kit online magazine (and mixed with a heavy punch of new exclusive material). It is packed with a feast of material, ranging from interviews with fighter pilots (including the English Electric Lightning, stealthy F-35B and Mach 3 MiG-25 ‘Foxbat’), to wicked satire, expert historical analysis, top 10s and all manner of things aeronautical, from the site described as:

“the thinking-man’s Top Gear… but for planes”.

The solid well-researched information about aeroplanes is brilliantly combined with an irreverent attitude and real insight into the dangerous romantic world of combat aircraft.

FEATURING

-

-

-

- Interviews with pilots of the F-14 Tomcat, Mirage, Typhoon, MiG-25, MiG-27, English Electric Lighting, Harrier, F-15, B-52 and many more.

- Engaging Top (and bottom) 10s including: Greatest fighter aircraft of World War II, Worst British aircraft, Worst Soviet aircraft and many more insanely specific ones.

- Expert analysis of weapons, tactics and technology.

- A look into art and culture’s love affair with the aeroplane.

- Bizarre moments in aviation history.

- Fascinating insights into exceptionally obscure warplanes.

-

-

The book will be a stunning object: an essential addition to the library of anyone with even a passing interest in the high-flying world of warplanes, and featuring first-rate photography and a wealth of new world-class illustrations.

The book will be a stunning object: an essential addition to the library of anyone with even a passing interest in the high-flying world of warplanes, and featuring first-rate photography and a wealth of new world-class illustrations.

Rewards levels include these packs of specially produced trump cards.

Rewards levels include these packs of specially produced trump cards.

Pre-order your copy now right here

I can only do it with your support.

Pre-order your copy now right here

I can only do it with your support.

The Top 34 pilot moustaches

Along with a sense of dash, a disrespect for authority and a dog, the male pilot should have a moustache. When we asked our readers for their suggestions for the top 10 pilot moustaches, we were stunned by the huge response. With this in mind, we have grown the list from 10 to a great hairy 34!

(note to US readers: we are talking about mustaches)

34. Dick Dastardly “Curses, foiled again!”

Dastardly’s appearance is based on Sir Percival Ware-Armitage from ‘The magnificent men in their flying machines’ (played by Terry-Thomas). Dick is penalised for not being real.

33. Chesley Sullenberger ‘Hudson-ducker proxy’

Hero and a gentleman he may be, but the ‘Angry Neighbour’ is not a stylish moustache.

32. Chief Instructor CDR Mike ‘Viper’ Metcalf

Metcalf mastered the ‘your mum’s new boyfriend‘ look but as he did not exist outside the homoerotic naval recruitment film ‘Top Gun’ he has not received a high ranking.

31. Col. Chris Hadfield ‘Cosmic busker’

“You know science can actually be fun…kids, where are you going?”

Orbiting Canadian busker Hadfield sports the ‘Scientist Uncle’ as also sported by your scientist uncle. Though being a spaceman is very impressive, this upperlip hair is far too sensible for this contest.

30. General Guishi Nagoaka ‘Hirsutie cutie pie’

The second largest moustache in the world at the time, but alas, cheeky Nagoaka was not a pilot — though he did pioneer some aspects of balloon warfare. According to his wife, the moustache was unbearably tickly on her thighs.

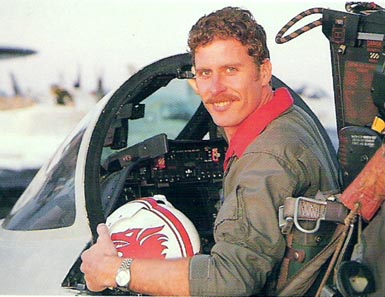

29. C.J. ‘Heater’ Heatley ‘Strawberry Top Gun’

F-14 pilot, Top Gun instructor and photographer Heatley took pictures that inspired the Top Gun film. All very well, but his thespian moustache seems too conventional to earn many points despite its excellent condition and strawberry blond hue.

28. Adolf Galland ‘Gallanded Gentry’

![Oberst Galland [Postkarte mit gedruckter Unterschrift]](https://hushkit.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/bundesarchiv_bild_146-2006-0123_adolf_galland.jpg)

104 aerial victories for the Luftwaffe and a tidy moustache.

27. Wing Commander Robert Stanford Tuck ‘Tuck shop’

A classic fighter pilot look from Tuck here. After an extremely eventful World War II he made friends with Adolf Galland in later life and had a mushroom farm.

26. Hans Von Dortenmann ‘Focke!’

Twat

This twat shot down 38 aircraft that were fighting the Nazis. He killed a relation (Tempest pilot F/Sgt Coles of 274 Sqn ) of the author — which is probably going to lose him some points in this moustache contest.

25. Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir John Cotesworth Slessor ‘Headmaster wants to see you’

If F-35 pilot Scott Williams hadn’t suggested Slessor’s inclusion on this list, it’s doubtful he would have made it (based on the image above anyway). Looking like the man who has just interrupted you sleeping with his wife, his stubbly shadow is below par.

24. René Fonck ‘Fonck you I won’t do what you tell me’

In World War I, two American pilots bet Fonck a bottle of champagne that one of them would shoot down an enemy plane before he did. Fonck lost the bet, but rather than pay it off, he convinced the Americans to change the terms of the bet so that whoever shot down the most Germans that day would win. Fonck went on to shoot down six enemy aircraft before the sun set. He become the top Allied Ace, with around 100 kills despite his unassuming moustache.

23. Glenn Curtiss ‘Curtiss may field first amphibious aircraft’

Peaky Blinders-style bully boy Glenn Curtiss did everything, if you don’t know him already, have a look on Wiki. Even with his busy life he kept time to maintain a really tough tash.

22. Bob Hoover ‘Not the KFC guy’

He could pour a cup of tea while performing a 1G barrel roll, and was one of the best pilots ever. Fairplay and a good ‘tash.

21. Charlie Brown ‘Peanuts’

Not to be confused with Charlie Brown from the Stigler incident , this Brown is a warbird pilot and owner of a pitch perfect handlebar.

20. Paul ‘Pablo’ Mason ‘The Mighty Fins’

Outspoken Gulf War veteran Pablo Mason was a Tornado pilot. As well as sporting a large moustache à la hongroise – a Saxon warlord kind of a thing – he was fired from being an airline pilot for being too cool*. High scorer here.

*He let a passenger on a charter flight onto the flightdeck to allay the passenger’s fear of flying, something which was banned following 9 11. He had previously stripped to his underwear in a protest at overly fussy airport security.

19. Roscoe Turner ‘Roscoe Turner Overdrive’

Somewhere between Dali and Vic Reeves, the surreal majesty of Turner’s Small Handlebar/Dali ‘tash look deserves celebration. Air-racing, lion-owning, DFC-winning Turner was a pretty amazing guy all round.

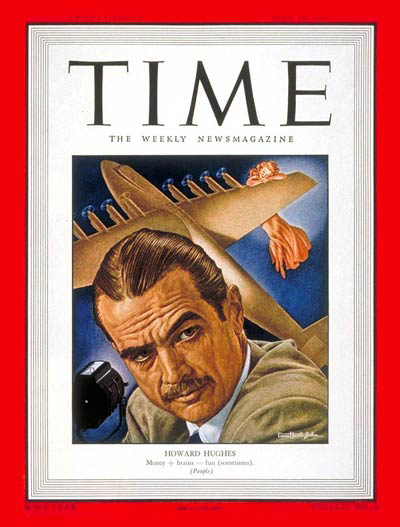

18. Howard Hughes ‘Hunky Hughes’

As well as collecting his own pee in jars and wearing Kleenex boxes for slippers, Hughes had an excellent understated moustache. Good to think of Hughes when considering if people like Bruce Wayne really exist.

17. Mike Napier ‘Hairy Tonka’

Mike Napier’s solid ‘Nigel Mansell’ is rocksteady at low-altitude, perfect for flying a Tornado GR.1

16. Jimmy ‘Wacko’ Edwards

Dakota pilot and entertainment star, Edwards’ poetic lip border is a joy.

Dakota pilot and entertainment star, Edwards’ poetic lip border is a joy.

15. Captain O P Jones ‘Jimmy Hillfiger’

Enter a caption

Charismatic spiritual father to all British airline pilots, Jones was feared and revered. When the HP.42 he was flying was badly hit by lightning, jamming the cockpit door shut and damaging the rear of the aircraft, he reassured passengers by sliding a note through a crack in the door. Despite this he has brought a piratical beard to a moustache contest and cannot be scored highly.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from Hush-Kit along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here

14. Adolphe Pegoud

Insouciant as fuck, Pegoud catches the carefree elegance of French heroes with his rakish handlebar. He was the first fighter ace in the world, the first person to parachute from an aeroplane and the second (not the first as believed at the time) pilot to perform a loop. He was shot down and killed by a former pupil in 1915 at the tender age of 26.

13. Group Captain Mandrake

Peter Sellers in Stanley Kubrick’s DR. STRANGELOVE (1964). Credit: Sony Pictures.

Failing to avert an apocalypse has never been done as stylishly as Peter Sellers’ Mandrake did it in the 1964 Dr Strangelove. I’m not sure this moustache was real, I know that Mandrake himself was not – so low points here.

(For reasons that remain unclear, ‘Mandrake’ is also the nickname of the editor of a popular aircraft magazine.)

12. Wiley Post ‘Post Modern’

Pionnering the pressure suit, discovering the jet stream and decorated with a rakish little moustache, Post had it going on.

11. Muhammad Mahmood Alam

“I may look like a supply teacher but I’m very good at what I do.”

Rumoured to have destroyed six IAF Hunters in one sortie — and with nine kills to his name, Alam was a hero to the Pakistan Air Force. The status of this F-86 pilot should not delude us into over-estimating his, at best, functional moustache.

12. Count Francesco Baracca ‘Ferrario’

Do not mess with Baracca. The Red Baron was not the only aristoric ace of World War I, Count Baracca had 34 confirmed kills and a no nonsense cold-blooded moustache. He painted his family crest on the side of his aircraft, a black prancing horse, which inspired the Ferrari’s iconic logo. He flew the Nieuport 17 and then, from March 1917, the SPAD VII.

11. Hugh Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard ‘Trenchard’s Furry Friend’

You can almost imagine Trenchard’s 1000-yard stare looking back at you as you catch him scrumping apples from your garden. History will judge a man who was an early advocate of strategic bombing and one of the architects of the British policy on imperial policing through air control as a man with a workmanlike facial caterpillar.

10. Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh C T Dowding ‘Dowdy-Dudey’

Dowdy Dowding was a spiritualist, a single parent, theosophist, anti-vivisectionist and a vegetarian — but his headmaster tash was not sexy. He was, however, very important in the Battle of Britain.

9. Gervais Raoul Lufbery — ‘Plucky Gervais’

Another insouciant individual who looks like he could only smoked to give himself a break from kissing and reading philosophy, Lufbery was a French-born half-American who volunteered to fight before the US entered the war. Unlike many of the rather posh rich Americans who fought as early volunteers, he was from a humble background having worked in a chocolate factory before the war. I almost forgot to mention his moustache- which is a micro-‘Lampshade’, and has a certain something.

8. Squadron Leader A H Rook  Leading a fighter squadron in Russia in 1941 demands a particularly brave moustache, so the RAF sent Rook. Good work.

Leading a fighter squadron in Russia in 1941 demands a particularly brave moustache, so the RAF sent Rook. Good work.

7. Squadron Commander the Lord Flashheart

Lothario, brawler and the mad bastard hero of the RFC, Lord Flashheart had an excellent handlebar moustache but loses points for being imaginary.

6. Wing Commander Roger Morewood

Perfect

Morewood — one of the last of the Few (he died in 2014) and rocker of a perfect RAF handlebar. The platonic ideal of the dashing fighter pilot, Morewood is a heavy hitter in pilot moustache world as well as having a name any male porn actor would die for.

5. Air Cmde Suren Tyagi

![Surensir[1]--621x414](https://hushkit.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/surensir1-621x414.jpg)

Come to ‘Fishbed’ eyes.

The Indian Air Force is an organisation that prioritises excellent moustaches over everything else (certainly over sensible procurement programmes). Thanks to this policy, Tyagi has created this luscious ‘Imperial’ style moustache, the perfect accoutrements for sitting in a MiG-21 or blasting a quail with a blunderbuss.

4. Flying Officer ‘Osti’ Ostaszewski-Ostoja

In the September 1939 campaign, Osti fought in the Polish “Dęblin Group”, a desperate last-ditch defence force organised by instructors of the Fighter Pilot School in Ułęż. He later fought as a Spitfire pilot in the RAF. Excellent jawline and full moustache.

3. Flight Lieutenant (Flt Lt) Karan Kohli ‘Dali Fulcrum’

Moustaches are an integral part of tradition and folklore in several parts of India, imbuing the grower with respect, honour and above all, a look that speaks of masculinity. Kohli can perform the famous Cobra manourvre in his MiG-29 using his moustache alone, which is pretty impressive. This is also an excellent moustache – so points all round.

2. Robin Olds ‘Olds pilot and bolds pilot’

Tom Hardy? Nope, Robin Olds.

You don’t get more USAF than Robin Olds, having fought with aplomb in both the P-38 and P-51 in World War II — and later the F-4 in Vietnam. His extravagantly waxed non-regulation) handlebar moustache was an act of open defiance to authority and started a fashion that swept across the Air Force. “It became the middle finger I couldn’t raise in the PR photographs. The mustache became my silent last word in the verbal battles…with higher headquarters on rules, targets, and fighting the war.”

When he was finally given a direct order to shave he did, which inadvertently inspired the Air Force tradition of “Mustache March“, in which airmen worldwide show solidarity by a symbolic hairy protest month against Air Force facial hair regulations. The moustache itself was a masterpiece of style, authority and dash.

- Orville Wright ‘Wright said Fred’

The first aeroplane pilot in the world had an excellent moustache, Orville’s magnificent face candy matching his contribution to world history. Years later it would inspire bland women on Tinder to don fake moustaches to demonstrate their lack of personalities.

Dear reader,

This site is in danger due to a lack of funding, if you enjoyed this article and wish to donate you may do it here. Even the price of a coffee a month could do wonders. Your donations keep this going. Thank you.

Follow my vapour trail on Twitter: @Hush_kit

You may enjoy these articles:

Top Combat Aircraft of 2030, The Ultimate World War I Fighters, Saab Draken: Swedish Stealth fighter?, Flying and fighting in the MiG-27: Interview with a MiG pilot, Project Tempest: Musings on Britain’s new superfighter project, Top 10 carrier fighters 2018, Ten most important fighter aircraft guns

The Supersonic Rotor Helicopter

Today, thanks to former Head of Future Projects at Westland Helicopters, Dr Ron Smith, we have gleaned further information on this intriguing, and potentially world-beating, project.

Today, thanks to former Head of Future Projects at Westland Helicopters, Dr Ron Smith, we have gleaned further information on this intriguing, and potentially world-beating, project.

“The Supersonic Rotor Helicopter. this was a project

completed by the long-term Future Project Office prior to my joining

Westland in October 1975. A report summarising the work was needed to

secure contract payment and I was tasked with pulling it together

(based on the work already conducted by others).

The SSRH proposition is based on the fact that if you increase the

rotor tip speed, the retreating blade stall boundary goes out to a

higher helicopter forward speed. (It’s a function of the ratio of

forward speed to tip speed, which is known as the Advance Ratio).

Suppose the tip speed is Mach 0.6 and at a particular blade loading

(think weight), the retreating blade limit is at an advance ratio of

0.3. That means that retreating blade stall will occur at Mach 0.18

(about 230 mph). In this case, the VNE might be say 210 mph (10%

margin).

If you double the tip speed to M=1.2, you can, in principle, fly at the

same advance ratio at double the speed (roughly 400 mph).

The study report (early 1976) looked at the shock wave propagation

geometries and a relatively basic performance calculation, in the

context of various designs targeted at naval roles. A range of

different tip Mach numbers were studied. WG32 was one of the sample

layouts (looking at them now, it appears that single, twin and three

engine variants were schemed). As far as I can tell, they were not

allocated separate WG numbers.

The obvious potential issues would be external noise and high power

requirements. But, in principle, it ought to work.

Although I wrote the report, I was not involved with any customer

meetings, but the feedback I was given by the Research Director was

that both he and the customer were very pleased with the report.

This was a piece of research to examine feasibility and highlight risks

and issues. I would imagine that it was felt that there was too much

risk to go down this route when conventional helicopter solutions could

probably provide adequate operational performance with lower risk in a

shorter timescale.

(Studies had already been completed on WG26 (Multi-Role Fleet

Helicopter) which went on via WG31 (Sea King Replacement) and WG34 to

become EH101 / Merlin).

I was not involved in any of these airframe studies, other than some

limited supporting work that I contributed to, in respect of the stall

flutter analysis of what became the BERP rotor blade.”

If you wish to see more articles like this in the future please donate here. Your donations, how ever big or small, keep this going. Thank you.

Follow my vapour trail on Twitter: @Hush_kit

-

Have a look at How to kill a Raptor, An Idiot’s Guide to Chinese Flankers, the 10 worst British military aircraft, The 10 worst French aircraft, Su-35 versus Typhoon, 10 Best fighters of World War II , top WVR and BVR fighters of today, an interview with a Super Hornet pilot and a Pacifist’s Guide to Warplanes Want something more bizarre? The Top Ten fictional aircraft is a fascinating read, as is The Strange Story and The Planet Satellite. The Fashion Versus Aircraft Camo is also a real cracker. Those interested in the Cold Way should read A pilot’s guide to flying and fighting in the Lightning. Those feeling less belligerent may enjoy A pilot’s farewell to the Airbus A340. Looking for something more humorous? Have a look at this F-35 satire and ‘Werner Herzog’s Guide to pusher bi-planes or the Ten most boring aircraft. In the mood for something more offensive? Try the NSFW 10 best looking American airplanes, or the same but for Canadians.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from Hush-Kit along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here

First footage of debut RAF F-35 exercise (from F-15E cockpit, featuring Rafale Cs)

Spitfire to Berlin? – Making Supermarine’s Finest an Escort Fighter

Could the Spitfire have equalled the Mustang in range and capability as an escort? Paul Stoddart examines some development options and suggests what might have been achieved.

|

Notes: All fuel capacities stated in this article are in Imperial gallons (equal to 1.20 US gallons). Fuel tank capacities (and other aircraft figures) often vary somewhat from source to source. The author has used either the most common or the most authoritative figure. The actual variations are, in any case, so small as to make no difference to the essential argument and findings. |

“The war is lost”, said Luftwaffe chief Herman Goering, on seeing Mustangs flying over Berlin. It was a remarkable achievement, a single-engined fighter with the range of a bomber. P-51s based in south-east England could fly the 1,100-mile round trip yet still win air superiority deep in Germany. The first such missions were flown in March 1944 and they were decisive. Merlin-powered Mustangs enabled the USAAF Eighth Air Force to prosecute its daylight campaign without the crippling losses it endured during 1943. The question remains, could Spitfires have flown that mission and flown it a year earlier? Could the Mk IX have taken on that role from the autumn of 1942? It is arguable that earlier success of the Eighth’s campaign would have hastened the end of the war in Europe. Bringing VE-Day forward even by a few months would have had significant implications and benefits; in particular, a smaller proportion of Central Europe might have fallen under Soviet control. The distinguished historian, Hugh Trevor-Roper once commented, “History is not merely what happened; it is what happened in the context of what might have happened. Therefore it must incorporate the might-have-beens.” An escort Spitfire was a might-have-been with much potential but before assessing the possible development routes, the actual design and development of the aircraft should be considered. To put the analysis in context, the role of the escort in the Eighth’s campaign will also be described.

Spitfire: Range on Internal Fuel

Although the Spitfire remained in the front rank of fighters throughout World War II, it never made the grade as a long-range escort. Specified as a short-range interceptor with the emphasis on rate of climb and speed, it is unsurprising that fuel load was not the Spitfire’s strongest suit. Throughout its life, the core of the Spitfire fuel system remained essentially similar although with several variations on the theme (See table 1). The Mk I carried 85 gallons of petrol internally in two tanks immediately ahead of the cockpit. The upper tank held 48 gallons and the lower 37. This arrangement was used in the majority of the Merlin fighter marks: II, V, IX and XVI. (By comparison, the Bristol Bulldog of 1928, with only 490 hp, carried 106 gallons). Later examples of the Mk IX and Mk XVI featured two tanks behind the cockpit with 75 gallons (66 gallons in the versions with the cut down rear fuselage). The principal versions of photo-reconnaissance Spitfires used the majority of the leading edge structure as an integral fuel tank holding 66 gallons per side. As this required the removal of the armament, it was not an option for the fighter variants. Capacity was increased in the Mk VIII (which followed the Mk IX into service) with the lower tank enlarged to fill its bay and holding 48 gallons. Each wing also held a 13-gallon bag tank in the inboard leading edge (between ribs 5 and 8) to give a total internal load of 122 gallons, a 44% increase on its forerunners. Eighteen gallon leading edge bag tanks were also fitted in some late Mk IXs. Fitting the Griffon in the Spitfire’s slim nose displaced the oil tank from its original ‘chin’ position to the main tank area. This reduced upper tank capacity by 12 gallons but all Griffon Spitfires, bar some Mk XIIs, featured the 48-gallon lower tank. It is worth noting that the PR Mk VI had a 20-gallon tank fitted under the pilot’s seat although no other mark of Spitfire appears to have used this option. On 85 gallons of internal fuel, the Mk IX had a range of only 434 miles; the Mk VIII, reaching 660 miles on 122 gallons, was still short on reach.

TO AVOID DISAPPOINTMENT ORDER YOUR COPY OF THE HUSH-KIT BOOK OF WARPLANES TODAY

Table 1. Spitfire Internal Fuel Capacity

Spitfire Range Extension – External Fuel

The slipper tank was the standard range extender on the Spitfire and some 300,000 were built in a variety of capacities and materials. Fitted flush on the fuselage underside ahead of the cockpit, the slipper tank was essentially a trough whose depth varied in proportion to volume. The 30, 45 and 90-gallon versions were used on fighter missions with the 170-gallon tank reserved for ferry flights only. The drag penalty imposed by slipper tank carriage was relatively high compared to the later ‘torpedo’ style drop tanks that were mounted on struts clear of the fuselage (see table 2). Compared with the slippers, the torpedoes were little used. All tank types could be jettisoned although this was normally only done when operationally imperative.

In the USA, two Mk IXs were experimentally fitted with Mustang 62-gallon underwing drop tanks. These were of metal construction and of teardrop form. The Aircraft & Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) at Boscombe Down tested the jettison properties of this tank from the Spitfire. At 250 mph, the tanks jettisoned cleanly but at 300 mph the tail of the tank rose sharply and struck the underside of the wing heavily enough to dent the skin. Although this failing was presumably not beyond correction, the 62-gallon tank appears not have been adopted for operational use. Nor has the author found any record of even a trial fit of the underwing 90-gallon Mustang tank on the Spitfire. These tanks were of cylindrical form and made of a plastic/pressed paper composite. Filled just before use, they had only to remain fuel tight for the first two hours or so of the sortie after which they would be jettisoned. Unlike a discarded metal tank, the plastic/paper versions were of no value to the enemy and, being ‘one-use’ only were routinely jettisoned when empty.

|

Slippers and torpedoes – Spitfire drop tanks |

||||

|

Tank capacity (gal) |

Tank type |

Total tank drag (lb) at 100 ft/sec at sea level 100 ft/sec = 68 mph |

Tank drag (lb) at 100 ft/sec at sea level per 30 gal |

Relative tank drag at 100 ft/sec at sea level per 30 gal where 45 gal torpedo is unity |

|

30 |

Slipper |

6.7 |

6.7 |

3.53 |

|

45 |

Slipper |

7.0 |

4.7 |

2.47 |

|

90 |

Slipper |

8.8 |

2.9 |

1.53 |

|

170 |

Slipper |

35.0 |

6.1 |

3.2 |

|

45 |

Torpedo |

2.8 |

1.9 |

1.0 |

|

170 |

Torpedo |

8.6 |

1.5 |

0.79 |

Table 2. Spitfire Drop Tanks: Capacity and Drag.

The Need for Long Range Escorts

The greatest need (and opportunity) for a long-range escort Spitfire was between August 1942, when the Eighth Air Force began its daylight campaign over Europe, and early 1944 when the Merlin Mustang appeared in strength. In August 1942, the Mk IX Spitfire was Fighter Command’s leading interceptor but, as it had only been in service for a month, the less capable Mk V still made up the bulk of front line strength. The Eighth’s first target (using the B-17E Flying Fortress) was the French town of Rouen and, given its proximity to England, Spitfires provided the escort. For targets deeper in Europe, the Spitfire’s short range was a severe limitation and precluded it as an escort. P-38 Lightnings arrived in the UK during the summer of 42 but this large aircraft (its empty weight was double that of the Mustang’s) was at a disadvantage in combat against the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and the nimble Focke Wulf Fw 190. The P-47 Thunderbolt began escort duties in April 1943 but even with 254 gallons of internal fuel (three times the Spitfire’s load) this thirsty beast lacked the range for deep escort. Adding a 166-gallon drop tank significantly increased the Thunderbolt’s radius of action (though not to Mustang standards) and long-range escort missions were flown from April 1943. Although a capable high level fighter, at low and medium altitudes the P-47 could not match the defending German interceptors for climb or manoeuvrability. It was the advent of the Merlin Mustang in December 1943 that firmly shifted the balance in favour of the Eighth Air Force.

During 1943, the Eighth suffered such heavy casualties as to make deep raids unacceptably costly.

The figures are sobering. In April, during a raid on Bremen, 16 bombers were lost out of 115; a loss rate of 14%; 4% is considered the maximum loss that can be sustained in the medium and long term. In June, 22 bombers were lost out of 66 (33%) and in July, 24 from 92 (26%) were downed; the targets were Kiel and Hanover respectively.

The case that fighter escort could have helped shorten the war is supported by the example of Schweinfurt. Lying to the east of Frankfurt, Schweinfurt was the centre of ball bearing production in wartime Germany. Ball bearings are essential for armaments and Allied target planners correctly identified the Schweinfurt plants as being crucial to the Nazi war effort. A raid in August 1943 cut production by 38%. According to Albert Speer, the Reich Minister of Armaments, prompt further attacks would have had a severe, even catastrophic, effect on the Nazi war machine. In the event, the heavy losses of the first raid delayed the second to October by which time production had been built up again. Despite this, the second raid reduced output by 67%. A further large-scale raid might well have been decisive but American losses were so severe that there was no follow-up. Of 291 bombers in the October raid, 60 were shot down (21%) and 138 damaged, adding up to a total casualty rate of 68%. Had an effective escort fighter been available during 1943, the frequency and effectiveness of those raids (and others) would have been much increased.

Planning For and Building Long Range Escorts

The vulnerability of daylight bombers to fighter defences was a lesson painfully learned by the RAF in the first two years of the War. As a result, Bomber Command re-directed its force to the night campaign that continued into 1945. The USAAF began its daylight campaign with the belief that the firepower of the B-17 would be sufficient defence. Even had that been true, an escort fighter would still have been beneficial. Obviously, the planning and build-up for the campaign began well before August 1942. At that time, the Spitfire was the leading Allied fighter and greater effort should have been applied to increasing its range so that it could operate deep in Europe as an escort. It was employed when targets in France were attacked so clearly the value of an escort was recognised. Supermarine faced the twin challenges of building sufficient Spitfires for the front line while also developing successor marks of greater performance. Concurrent development and manufacture in America would have substantially increased the resources available. There were precedents for such a policy. The American car company Packard produced over 55,000 of the 168,000 Merlin engines built; Canadian companies also supplemented production of the Hawker Hurricane and Avro Lancaster. There was no insurmountable obstacle to America-based Spitfire manufacture. Options might have included Curtis taking on Spitfire production in place of the distinctly average P-40 or the Spitfire replacing the P-39 Airacobra at Bell. American resources would have speeded the development of the Spitfire beyond the Mk V and could have aimed that development at stretching the range for the escort role.

Spitfire versus Merlin Mustang

Supermarine had some success during the War in extending the Spitfire’s range but it did not come close to matching the P-51. Put simply, the Mustang flew far further because it carried much more fuel and had less drag. This article will concentrate on fuel load but the drag difference is worth addressing briefly. At the same throttle setting, a Merlin Mustang would fly 30 mph faster than a Merlin Spitfire of equal power. The P-51 gained significant thrust from the air passing through its radiator such that its net coolant drag was only one sixth that of the Spitfire. (See Lee Atwood’s article in Aeroplane May 99). Building this system into the Spitfire would have resulted in effectively a new aircraft but increasing the fuel load was certainly feasible. Incidentally, Supermarine produced a design proposal involving moving the radiators from under the wings to the fuselage underside just aft of the cockpit; clearly the Mustang had been an object lesson. A company report in December 1942 claimed a 30 mph speed increase would accrue from that and certain other modifications but the scheme was taken no further.

The first Merlin powered Mustangs, the P-51B and C, began operations from England in late 1943. At that time, the Mk IX Spitfire led Fighter Command’s order of battle. Both aircraft had 60-series Merlins of similar power output but their performance differed markedly (see table 3).

|

P-51C |

Spitfire IX (%age of P-51C value) |

|

|

Engine / Power hp |

V-1650-7 1,450 hp at take-off War emergency 1,390 hp at 24,000 ft |

Merlin 61 1,565 hp at take-off (108%) War emergency 1,340 hp at 23,500 ft (96%) |

|

Empty weight lb |

6,985 |

5,800 (83%) |

|

Normal loaded lb |

9,800 |

7,900 (81%) |

|

Max loaded lb |

11,800 |

9,500 (81%) |

|

Internal fuel Imp gal |

224 |

85 (38%) |

|

Range on internal fuel |

955 miles at 397 mph at 25,000 ft 1,300 miles at 260 mph at 10,000 ft |

– 434 miles (33%) at 220 mph at ? ft (85%) |

|

Air miles per gallon |

4.44 6.05 |

– 5.11 (84%) |

|

External fuel Imp gal |

180 (2 x 90 under wing drop tanks) |

90 (1×90 under fuselage slipper drop tank) (50%) |

|

Total fuel Imp gal |

404 |

175 (43%) |

|

Range on total fuel |

2,440 miles at 249 mph |

980 miles (40%) at 220 mph (88%) |

|

Air miles per gallon |

6.18 |

5.60 (91%) |

|

Speed mph at ht ft |

426 mph at 20,000 ft 439 mph at 25,000 ft 435 mph at 30,000 ft |

396 mph at 15,000 ft (93%) 408 mph at 25,000 ft (93%) |

|

Time to 20,000 ft |

6.9 min |

5.7 min (83%) |

|

Ceiling ft |

41,900 |

43,000 (103%) |

|

Armament |

4 x 0.5” 350 rpg i/b, 280 rpg o/b |

2 x 20mm 120 rpg, 4 x 0.303” 300 rpg |

|

Consumption is quoted in air miles per gallon (ampg) figures and is the average value for a specified case of fuel load, speed and cruising altitude. Note that both the Spitfire and Mustang were more economical when carrying drag inducing external tanks than when flying clean. This paradoxical point is explained by the fact that the longer range endowed by drop tanks resulted in the aircraft spending a greater proportion of the flight in the cruise, the most frugal phase of the sortie. |

||

Table 3. Performance Comparison: Spitfire Mk IX versus Mustang P-51C

Have you contributed to support this site? Please do have a look here to keep us going. Thank you

Despite an empty weight half a ton greater than the Mk IX, the P-51C had a useful speed advantage. In range, there was no comparison. On internal fuel alone, the Mustang almost equalled the slipper tank fitted Spitfire’s range and did so cruising 80% faster. The Mk IX’s only win was in time to height where its lower weight was advantageous. It is worth noting that the Mk XIV Spitfire required the 2,050 hp Griffon to equal the P-51D’s speed; its range was somewhat less than the Mk IX owing to the greater thirst of its 36.7 litre powerplant.

It should be noted that range figures in many reference books are potentially misleading, as those quoted are generally the aircraft’s absolute maximum under ideal conditions. In actual operations, fuel allowances must be made for take-off, climb, head winds, combat and diversion. The effect is to reduce the realistic operational radius of action to under half the maximum range. Note that the P-51C needed drop tanks to reach Berlin with enough fuel remaining for combat and return to base whereas its absolute range figure suggests it could fly a double round trip.

In his book Spitfire: A Test Pilot’s Story, Supermarine chief test pilot Jeffrey Quill describes an experiment in range extension. A Mk IX Spitfire was fitted with a 75-gallon rear tank plus a 45-gallon drop tank (presumably a slipper) for 205 gallons total. Quill flew a non-stop return flight from Salisbury Plain in southern England to the Moray Firth in northern Scotland. Owing to poor weather, the journey was entirely made below 1,000 ft, which is not the most economical cruising altitude. Distance covered equalled the East Anglia to Berlin return sortie of the Mustang. The flying time was five hours, suggesting the standard cruising speed of 220 mph was used for the 1,100-mile trip. However, with its 68-gallon rear tank, the P-51’s internal capacity was around 224 gallons. For long-range escort missions, it carried two drop tanks of 62 or 90 gallons each giving a total load of at least 348 gallons, ie some 70% more fuel than Quill’s experimental Mk IX. We must conclude that on 205 gallons, the Mk IX would have had little or nothing in reserve for combat when 550 miles from home. (Note that cruising at 20,000 ft would have reduced fuel consumption by 10% or more).

Spitfire fighters achieved similar distances to the Berlin mission during the War but only on ferry sorties. Mk Vs were flown from Gibraltar to Malta, a distance of 1,100 miles, ie equal to the England-Berlin round trip. A total of 284 gallons was carried: 85 gallons in the standard fuselage tanks, a 29-gallon rear fuselage tank plus a 170-gallon drop tank. The route was first flown in October 42 and the aircraft landed after 5¼ hours (210 mph ground speed, there was a slight tail wind) with 40 gallons remaining. The drop tank was not jettisoned and the average consumption was 4.51 ground miles per gallon, ie a maximum range of 1,278 miles in those conditions. A&AEE estimated the range of the Mk V with both the 29-gallon and ferry tank to be 1,624 miles assuming tank jettison (5.72 ampg); the range gain of 27% emphasises the drag of the big slipper tank. Achieving escort fighter range with the Spitfire was clearly possible but the bulky 170-gallon tank was not the answer.

As an aside, in their comprehensive tome Spitfire, The History, Morgan and Shacklady include a diagram of Mk V Spitfire range as an escort with the 90-gallon slipper tank. A 540 mile radius of action is claimed at a 240 mph cruise with 15 minutes allowed for take-off and climb plus 15 minutes at maximum power (ie combat). Starting from south-east England, such a radius takes in not only Berlin but also Prague and Milan. Maximum range with the 90-gallon external tank and 85 gallons of internal fuel is generally quoted as 1,135 miles with no allowance stated for combat and so forth. No Spitfire flew deep escort missions and this makes the claim for the Mk V having Berlin capability somewhat questionable.

As already stated, reducing the Spitfire’s drag to the Mustang’s level was not feasible in a realistic timescale but there was definitely potential to increase its fuel load. Here, the escort potential of the Mk IX will be assessed. The Mk IX entered service in July 1942 and was essentially a Mk V modified to take the two stage, two speed supercharged Merlin 60 series. It was rushed into production to counter the Focke Wulf Fw 190A-1 that had, since its appearance in July 1941, proved markedly superior to the Mk V Spitfire. The plan had been for the Merlin 60 to first appear in the Mk VIII, which was a more highly developed design with, inter alia, revised ailerons, a retractable tailwheel and leading edge fuel tanks. In the event, the loss of air superiority to the Fw-190 forced the stopgap Mk IX into being and, as is well known, it proved highly successful. Hence the Mk IX preceded the Mk VIII into service by 11 months.

Developing the Mk IX Escort

Beginning life with the standard 85 gallons of internal fuel, the Mk IX also used slipper drop tanks of 30, 45 or 90 gallons on combat sorties. Late production Mk IXs gained the 75 gallons of the rear fuselage tanks taking total internal fuel load to 160 gallons or 71% of the P-51’s capacity. Add the 90-gallon slipper tank and total fuel rises to 250 gallons. With 175 gallons (85 + 90), the Mk IX’s range was 980 miles at 220 mph. A total of 250 gallons is an increase of 43% but an equal increase in range should not be assumed without some thought. The added weight of the rear tanks and fuel (around 640 lb, an extra 7% in take-off weight) would slow the climb to altitude and increase the lift-induced drag. That would be balanced by the extra fuel extending the sortie time fraction spent in the cruise. A&AEE estimated the maximum range of the Mk IX with the 170-gallon ferry tank to be 1,370 miles (85 + 170 = 255 gallons, 5.37 ampg). As the 170-gallon tank was a high drag installation (some four times ‘draggier’ than the 90-gallon version, see Table 2) it is reasonable to allow our Mk IX its 43% range increase, ie 1,401 miles. This is confirmed by a Supermarine trial of the 85 + 75 + 90 gallon fuel load case that achieved ‘around 1,400 miles’. Thus the escort Mk IX would achieve 56% of the Mustang’s 2,440-mile range yet required 62% of the Mustang’s 404 gallons total load. This demonstrates the P-51’s low drag advantage, enabling it to fly 10 miles for every 9 flown by the Spitfire despite cruising almost 30 mph faster.

In addition to the above case described by Quill, the Mk IX was also the subject of a range extension experiment in America. At Wright Field, two Mk IXs were fitted with a 43-gallon tank in the rear fuselage, 16.5 gallon flexible tanks in each leading edge and a Mustang 62-gallon drop tank under each wing. Total internal capacity: 161 gallons; total fuel load: 285 gallons (oil capacity was also increased to 20 gallons). A still air range of approximately 1,600 miles was achieved. According to Quill, certain of the American structural modifications adversely affected aircraft strength so ruling out this scheme for production. What was the problem? Given that the Mk VIII and later marks had leading edge bag tanks as standard, any problem with that particular Wright Field modification could surely have been resolved. The Mk IX was cleared to carry a 250 lb bomb on the underwing station whereas a full 62-gallon tank weighed around 550 lb. Clearance of that tank should still have been possible albeit with a lower g-limit than when the bomb was carried.

Where else could internal fuel have been installed? The rear fuselage tanks hardly filled the space available but adding additional weight there would have moved the centre of gravity unacceptably far aft. Late production Mk IXs featured an 18-gallon Mareng bag tank in each wing although it is not clear how widely these wing tanks were fitted and used. There was also provision for 14.4 gallons of oil for long-range sorties in place of the standard 7.5 gallons. With rear fuselage and wing tanks, internal fuel capacity would have been 196 gallons, giving an estimated range of 1,002 miles. Add the PR Mk VI 20-gallon under-seat tank and the figures would have been 216 gallons and 1,210 miles. The 90-gallon slipper tank would take total fuel load to 306 gallons and range to 1,714 miles (70% of the P-51).

Could any more fuel have been carried in the wing? Maximum wing fuel was achieved in the photo-reconnaissance versions where the deletion of the armament allowed unfettered use of the leading edge. The fighters used flexible bag tanks but in the PR versions, the leading edge structure between ribs 4 and 21 was converted into an integral tank carrying 66 gallons per side. Late production Mk IXs had an armament of 2 x 20 mm Hispanos and 2 x 0.5” Brownings. The latter was fitted between ribs 8 and 9 with the cannon between 9 and 10. Could the integral tank been made in two sections, joined by pipework and with the armament in between? Such a tank would have comprised 15 bays compared to the 17 of the PR case. Assuming a volume of 80% of the full span PR tank, the fighter version would have held 53 gallons per wing, taking internal fuel to 286 gallons.

Table 4 presents actual measured and estimated ranges for various fuel loads. For the measured cases, the range achieved is divided by the fuel capacity to give the average ampg. For each estimate, an appropriate ampg figure is multiplied by the fuel load to give the range. This method is somewhat crude but offers an idea of the Mk IX’s potential.

|

Internal Main + rear + wings (total) (gal) |

External (gal) |

Total (gal) |

Range (miles) |

Air miles per gal |

Comment |

|

|

a |

85 + 0 + 0 (85) |

0 |

0 |

434 |

5.11 |

Internal fuel, early versions |

|

b |

85 + 0 + 0 (85) |

90 |

175 |

980 |

5.60 |

As above plus 90-gal slipper tank |

|

c |

85 + 75 + 0 (160) |

0 |

160 |

896 |

5.60 |

Internal fuel, later versions |

|

d |

85 + 75 + 0 (160) |

90 |

250 |

1,400 |

5.60 |

As above plus 90-gal slipper tank |

|

e |

85 + 75 + 0 (160) |

90 +2×62 |

374 |

2,020 |

5.40 |

As above plus 2 x 62-gal u/w tanks |

|

f |

85 + 43 + 33 (161) |

2 x 62 |

285 |

1,600 |

5.61 |

Wright Field trial |

|

g |

85 + 75 + 20 + 36 (216) |

0 |

216 |

1,210 |

5.60 |

Max internal capacity |

|

h |

85 + 75 + 20 + 36 (216) |

90 |

306 |

1,714 |

5.60 |

As above plus 90-gal slipper tank |

|

i |

85 + 75 + 20 + 36 (216) |

2 x 62 |

340 |

1,904 |

5.60 |

Internal plus 2 x 62-gal u/w |

|

j |

85 + 75 + 20 + 36 (216) |

90 +2×62 |

430 |

2,322 |

5.40 |

As above plus 90-gal slipper tank |

|

k |

85 + 75 + 20 + 106 (286) |

0 |

286 |

1,602 |

5.60 |

Integral tanks 53 gal per wing |

|

l |

85 + 75 + 20 + 106 (286) |

90 |

376 |

2,106 |

5.60 |

As above plus 90-gal slipper tank |

|

m |

85 + 75 + 20 + 106 (286) |

2 x 62 |

410 |

2,296 |

5.60 |

Internal plus 2 x 62 gal u/w |

|

n |

85 + 75 + 20 + 106 (286) |

90 +2×62 |

500 |

2,700 |

5.40 |

As above plus 90-gal slipper tank |

|

o |

85 +29 + 0 (114) |

170 |

284 |

1,278 |

4.50 |

Mk V in ferry fit. 170-gal slipper tank not jettisoned. |

Table 4. Spitfire Mk IX Fuel Load and Range Estimates

Note: Range and air miles per gallon (ampg) figures in normal font are from actual trials measurements.

Range and ampg figures in italics are estimates for the proposed fuel load cases.

On internal fuel alone of 216 gallons (g), the Mk IX might have reached 1,210 miles or almost three times the range on its original internal load of 85 gallons. This figure also bears comparison with the Mustang’s 1,300 miles on 224 internal gallons – albeit with the Mustang cruising at 260 mph to the Spitfire’s 220 mph (see Table 3). Adding the three external tanks (90 + 2 x 62) (j) takes the projected Mk IX beyond 2,300 miles and into the region where an escort mission to Berlin might have been possible. On internal fuel of 286 gallons (k), the Mk IX’s range would have been in the order of 1,600 miles rising to around 2,300 with the two 62-gallon drop tanks and 2,700 miles when the 90-gallon slipper was added as well. On this basis, Berlin was certainly within its radius of action.

Before a judgement is made, we must consider whether the Spitfire could have carried such a weight of fuel. Table 5 compiles the weight of a Mk IX with 216 gallons internal plus the three external tanks holding 214 gallons. At 9,856 lb it is some 4% above the 9,500 lb maximum take-off weight. Fitting the 45-gallon slipper tank in place of the 90-gallon version would have reduced total weight to 9,502 lb, fuel load to 385 gallons and range to 2,079 miles. However, the risk of the weight exceedance might have been considered worthwhile in return for the range benefit. The Wright Field modified Mk IX weighed 10,150 lb and the undercarriage was fully compressed under this load. In the 286 internal gallons case Mk IX, no allowance has been made for the weight of the integral tanks. Even so, total weight with the three external tanks is 10,467 lb or 10% above MTOW; such a load would probably have required the strengthened structure of the Mk VIII.

|

Internal 85 + 75 + 20 + 36 (216) |

Internal 85 + 75 + 20 + 106 (286) |

|||||

|

Empty |

5,800 |

Empty 1 |

5,850 |

|||

|

240 rd 20mm |

150 |

240 rd 20mm |

150 |

|||

|

1,400 rd 0.303” |

93 |

500 rd 0.50” |

150 |

|||

|

14.4 gal oil |

131 |

14.4 gal oil |

131 |

|||

|

Pilot & kit |

200 |

Pilot & kit |

200 |

|||

|

75-gal rear tank (estimated) |

100 |

75-gal rear tank (estimated) |

100 |

|||

|

Basic weight |

6,474 |

Basic weight |

6,581 |

|||

|

Internal fuel 216 gal |

1,555 |

Internal fuel 286 gal |

2,059 |

|||

|

90-gal slipper |

120 |

90-gal slipper |

120 |

|||

|

2 x 62-gal |

166 |

2 x 62-gal |

166 |

|||

|

External fuel 214 gal |

1,541 |

External fuel 214 gal |

1,541 |

|||

|

Total fuel weight |

3,096 |

Total fuel weight |

3,600 |

|||

|

Total weight |

9,856 |

Total weight |

10,467 |

|||

Note 1. Two 0.50” Brownings increase empty by 50 lb compared to four 0.303” Brownings

Have you contributed to support this site? Please do have a look here to keep us going. Thank you

Table 5. Spitfire Mk IX: Estimated Weight in Escort Role Configurations

Fuel Management and Centre of Gravity

Careful fuel management would have been important. The rear fuselage fuel moved the centre of gravity sufficiently far aft to make the Spitfire longitudinally unstable. As a result, the aircraft could not be trimmed, so tended to diverge in pitch and tighten into turns. These characteristics were certainly undesirable (the latter was unacceptable in combat) but could be tolerated in the early stages of a sortie, ie climb to height and the first part of the outbound cruise leg. A&AEE tests showed that when 35 gallons of the rear fuel had been consumed, longitudinal stability was regained. Conversely, additional leading edge fuel would have caused little problem, as it was far closer to the centre of gravity so causing only small changes in trim as it was consumed. The sequence of fuel use in an escort sortie might have followed this pattern:

Start-up, taxi and take-off with rear tank selected

Climb to height and cruise commenced on remaining rear tank fuel

Outbound cruise continued on underwing tanks fuel – jettisoned when empty (or on entering combat)

Combat on slipper tank fuel

Return on internal fuel

Conclusion

There was surely no insuperable obstacle to developing a long range escort version of the Spitfire. Wing tanks and rear fuselage tanks were used successfully albeit later in the war than was ideal. The use of the leading edge as an integral tank was also successful in the PR Spitfires and a two section version was surely not impossible. All the above options could have been applied to the Mk IX’s successors, in particular the Mk VIII and the Mk XIV, the leading RAF fighters in the final year of the war. The Griffon powered Mk XIV was an outstanding fighter and would have been a formidable escort over Germany. The Mk VIII served in the Far East, a theatre of operations where long range was invaluable.